The challenge of patient safety

In this reflection on my patient safety journey over the past 30 years, I will look at ways that the future generation of healthcare leaders, clinicians and managers or executives can ensure that patient safety becomes an integral part of what they do, within the genome of a safety belief system. This will make safety part of what is done in all daily activities. I will use a few patient safety stories to illustrate what can be done to make a difference.

Everyone has a story to tell. As you read the paper, I invite you to reflect on your own story and experience of patient safety and of your own safety and then consider how you feel. You will have experienced a “near miss” when you nearly harmed a patient or have experienced being burnt out. Some of you will have been involved in an adverse event in which a patient was harmed, with you being what we term a “second victim.”

In modern day healthcare the people who we call patients usually experience harm free care. However we harm up to 10-15% of patients, and this may be an underestimate as we can define harm in many different ways. The prevalence of avoidable harm varies and depends on how one defines avoidable [1]. Recent reports have indicated a higher level of up to almost 25% of inpatient care [2].

The papers by René Amalberti [3] and Charles Vincent [4] described their story on how to to investigate and learn from clinical incidents. They offer concrete ways to make this process a learning experience by taking a systems approach to adverse event investigations. In this paper I will build on their contribution with a perspective of what a clinician can do to build a safer system, where risk is managed proactively and harm is reduced, with a better experience for both the patient and the clinician. This will be based on my experience as a clinician and advocate for patient safety and quality in healthcare.

My story of patient safety

The history of patient safety is not new. The need to keep patients free from harm goes back to the code of Hammurabi in 1750 BC, and to the Hippocratic Oath Primum non Nocere - First do no Harm - in the 3rd -5th century BC [5]. However the modern approach to Patient Safety commenced around the turn of this century with the publication of the reports in the USA and UK [6], well after I graduated in 1979. This meant that patient safety theory was not taught in the medical school I attended. Nonetheless, I swore to uphold the Hippocratic Oath, a tradition that is currently not that widespread. I remember how solemn the ceremony was, although I had no idea whether harm was widespread or not. As we did not measure harm or adverse events. In those days it was assumed that just by being a professional one would be safe, a view many clinicians still hold.

However, I had an idea that healthcare was not as safe as was made out to be. In 1973 Ivan Illich published his prophetic book Limits to Medicine: Medical Nemesis - the Expropriation of Health [7]. In this polemic on the medical profession, Illich explored his belief that healthcare was harmful, creating iatrogenic harm in at least 10% of patients. He identified three type iatrogenic harm, all of which are relevant today. Clinical iatrogenesis is the actions that cause harm, as there was little evidence based medicine, social iatrogenesis is the medicalisation of health and life in general, and cultural iatrogenesis is where the beliefs of people about life, health and disease have been appropriated to support the first two forms of iatrogenesis [8]. As a result, doctors overtreat or mistreat their patients. The book shocked the medical profession and we were advised by our professors that there was no data to support Illich and that the book shouldn’t be read!

However we now know that, despite the lack of data, Illich underestimated the amount of harm that is actually caused by medical interventions. In those days it was assumed that “stuff happens” which we called unavoidable side effects, consequences, or adverse events. The healthcare science of patient safety had yet to be born.

Yet within two years of graduating, I experienced the first adverse event in which a trainee doctor inadvertently administered potassium chloride instead of sodium chloride to an infant with diarrheal disease, as the two vials were kept side by side. Mixing up the two vials was an easy human error to make. It was my responsibility to inform the parents that we had inadvertently killed their infant son. Although I was unaware of the significance of this event to me and was more focused the impact it had on the family, it was the start of the journey that has defined my life’s work.

Reflecting on that significant day, I see myself as the third victim in this incident- the infant and family being the first victim and the doctor and nurse the second. The trainee doctor and nurse lost confidence and ultimately their careers, all because it was viewed as human error rather than a systems design issue; patient safety as a science had yet to be born. This was a human factors and ergonomics failure in a high performing unit that was well organised, treating over 100 babies with diarrhoea a day, in a very efficient and effective way.

The development of Patient Safety Science

In modern medical practice over the past 40 years, there has been a move to develop a science of patient safety, with theories and methods to decrease harm. Most papers on patient safety are about the technical aspects of being safe. The initial focus was on managing adverse events - “how does one investigate a serious event” followed by answering the question of “how one can apply the theories and methods” to improve patient safety. Yet despite the rapid advances made in understanding of what to do, the implementation of patient safety initiatives has not been as good as it should be.

The World Health Organisation published the Global Patient Safety Action Plan in 2021, and in a review of the implementation of the plan found that few countries have a national strategy or had implemented the report’s recommendations [9,10]. Imperial College published a global review with similar results [11]. The failure to have an effective safety programme has many different reasons, one of which is that clinicians in the front line of care have yet to respond with enthusiasm to the patient safety challenge. Few clinicians will have read their own organisation’s patient safety strategy. Despite all the patient programmes, we are falling short. Key reasons for this problem include the lack of a patient safety culture, the pressures of work, the increasing complexity of healthcare, and the lack of leadership and managerial support [12].

The challenge for future generations of clinicians

The challenge is for the future generation of clinicians to know what to do to be safe, while delivering care in a complex and challenging environment. On reflection, I have identified several steps to make a difference based on experiences that have defined my career. As a more senior doctor, the first major clinical incident I was called on to address was in a small paediatric unit in rural England in 1994. A nurse had murdered three infants and attempted to murder another four. She was convicted of murder and a diagnosis of Munchausen by Proxy was given. Yet the issue was one of total systems failure. As patient safety science was in its infancy so the incident was seen as one “bad apple” in the system. I discovered clinicians who were burnt out, systems and processes that failed them and children and families who had experienced harm. And more importantly, as this was prior to the patient safety movement commencing, patient safety theory and methods were non-existent. Over the years I have encountered similar events that I have helped to investigate. From these I have identified the actions that follow. I invite you to consider how you can apply them to your setting.

Action 1: The importance of values: Ask “WHY” you should be safe

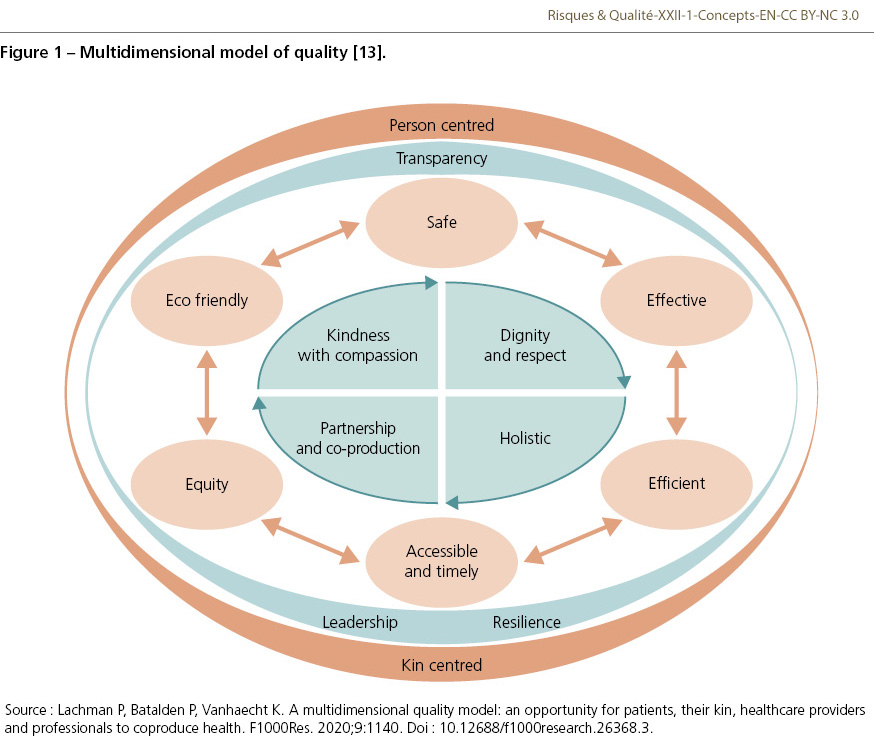

Patient safety is all about people i.e., the people for whom we give care, also known as patients and the people who provide care also known as healthcare providers. It is about relationships and the trust around those interactions. We enter medicine with the enthusiasm to make a difference and really believe that we can deliver harm-free care. Patients trust us to be safe. Yet, as care becomes more complex and the demand exceeds our ability to provide care, the attention to patient safety has become more difficult. Therefore, to be safe we need core values that we hold as our “north star” throughout our careers. I developed the multidimensional approach to quality to emphasise the importance of values to deliver safe high quality care as shown in Figure 1. Within the model, respect, kindness and compassion, holistic integrated care, transparency and coproduction of health are essential to deliver any of the domains of quality [13]. This requires the balancing of the different domains of quality while providing clinical excellence to achieve the outcomes one desires.

Climate change has been included in the model as this is both a quality and safety issue.

Action 2: Develop a safe culture

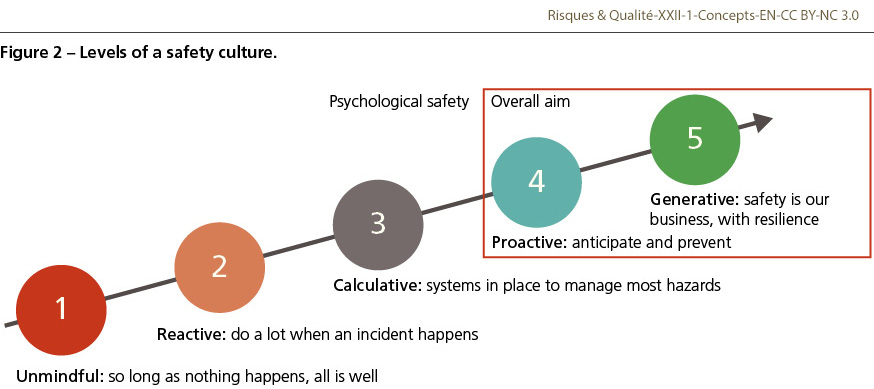

As noted by Federico [14], the culture of safety is the foundation of any safety system. Culture is what we believe and think and determines what we do and produce i.e., the outcomes of our actions. A safe culture cannot be assumed to exist, rather it needs to be nurtured and developed. In every patient safety event which I investigated, the key problem has been the absence of a safety culture, or rather the false assumption that a safe environment existed. Clinical teams need to actively ask “are we safe?” on a daily basis. Although culture is complex, I have found the Manchester Patient Safety Scale [15,16] to be a useful method for clinical teams to assess their own safety culture. One can distil this to asking five questions to determine whether the care is safe, which is important as indicated in Figure 2. When asking the question for each level, providing concrete examples helps the team to determine whether a safe culture exists or not.

If one considers each of the levels in Figure 1, one can see where one has to go to be safe. We may be generative in part of our work, e.g. in prescribing blood products, yet unsafe in other parts where we take more risk or do not pay attention to detail, e.g. in hand hygiene or prescribing. Most of teams are in the reactive or calculative zones, with systems in place but few are managing risk proactively. The aim of any patient safety programme is to move up the different zones so that safety is our daily business.

Action 3: Educate yourself for psychological safety

To achieve this, a safe culture requires an environment where all those involved in clinical care feel safe, both patients and healthcare workers. Psychological safety which was introduced by Edmonson [17] is creating a work environment in which people bring their whole selves to work, feel safe to speak up and challenge. This concept has gained increasing traction over the past few years [18]. In a recent paper, it has been proposed that we need to learn the competencies for psychological safety, just as we have to be competent in our clinical skills [19]. My view on this is that we need to inject psychological safety into the genome of the healthcare worker from the start of training so that we ensure that safety becomes what they naturally do without thinking [20]. This will help the challenge of burnout and will build resilience in the system.

Action 4: Equip yourself with safety skills especially human factors

It is clear to me that patient safety science is as important as any other core subjects that are routine in medical education such as anatomy, pathology and physiology [21]. Unfortunately, this is not the case in most training programmes and if present in a curriculum, the time allocated is still far too short. Curricula in patient safety have been developed and can be applied within undergraduate and post graduate training. I urge you to demand that this be included in your training. At a minimum there should be comprehensive courses in human factors and ergonomics integrated into our education [22].

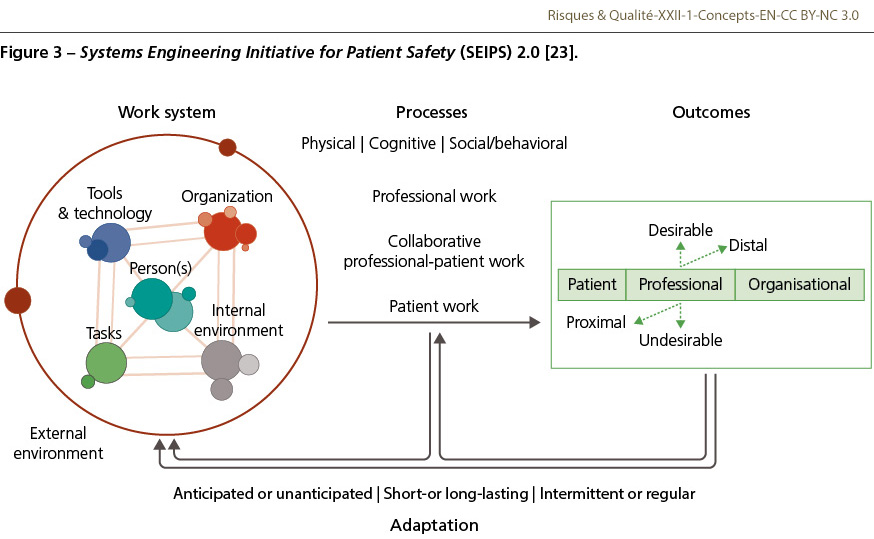

As the complexity of healthcare increases, human factors training is essential and not just an option. I like the relative ease of use of the SEIPS model [23] which can be applied at every level of an organisation and be used to teach human factors to clinical teams (Figure 3). It complements other programmes such as CREW management [24] and Team Steps [25].

Clinical teams can use this model every day to make safety their business model. Three questions to ask:

- How is our work systems (or team) operating, e.g. do we have the right staff and patients, can we perform the tasks required with the tools we have, and how is our work organised in the work environment?

- Are processes reliable, e.g. are the clinical guidelines followed as agreed?

- Measure the clinical outcomes both desired and undesired, including patient experience, e.g. ask what are we doing well and not so well.

If this is done every day the team is on the road to safer care.

Action 5: Empower patients to be equal partners through coproduction and shared decision making

Recently the concepts of coproduction and Shared Decision Making [26] have become important interventions in healthcare. The key is to allow patients and their families to define quality and safety. As a clinician I have always regarded the children and parents in my care to be equal partners in their care. I also realised that to keep them safe one needed to break down the hierarchical nature of the clinician-patient relationship by giving parents and children the agency to control their health and manage their disease. An example is a patient being able to decide what course of action suits their own lived experience. Self-management and deciding on best treatment options together meant that there would be safer outcomes. The WHO Patient Safety Charter [27] which has been developed by patients is a good place to start when you consider how you can make a real difference in the delivery of care. People need psychological safety to be in control and the courage to change the traditional model of care.

Action 6: Place equity at the core of all actions

Inequitable care is pervasive in every society and we need to recognise that the social determinants in health must be a focus in all that we do. In my formative years in South Africa it became clear to me that the social determinants of health had a major impact on clinical presentations and resultant outcomes. This has influenced a commitment to ensure that everyone has an equal chance to receive safe care. Yet this is not true in patients [28]. People from different backgrounds, be it ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, or where they live, have worse outcomes and more adverse events. As clinicians we cannot avoid this challenge and we have to always ask the question “have I addressed the equity challenge?”

Action 7: Harness the opportunities of new technologies to ensure diagnostic safety

Diagnostic safety [29] is a new challenge and is the latest WHO patient safety theme. Innovation has always been part of healthcare, and the future has many opportunities, with digital health and artificial intelligence to improve healthcare. This is especially important in the area of diagnostic safety. However, the expansion of telemedicine, along with the use of artificial intelligence in diagnosis has raised new safety challenges. While it is early days in this rapidly moving field, the potential is great and we need to embrace future opportunities [30].

Action 8: We must all be leaders for safety and develop a learning system

The final action underpins all the others. Patient safety cannot happen unless everyone leads for patient safety. The complexity of patient safety and the concept of the problem of many hands where no one takes responsibility for the safety is a challenge to overcome [31]. Every clinician needs to be a leader to make a difference, not only for the individual person treated but for the team and organisation. Developing a learning system where we learn from what works well and also from clinical incidents and adverse events is the outcome we should aim to achieve. To reach this type of system I developed the SAFE intervention [32] that provides clinical teams a format to ensure that they lead on patient safety and know how to translate the complex theory into meaningful action. In this process huddles are held a few times a day to implement different safety theories and methods. The huddles are based on the Vincent model of measuring safety with the addition of asking what is working well [33]. Results have shown better teamwork and morale and improved outcomes. An example is on a unit in Mozambique in which the team decreased the number of deaths within 24 hours of admission from 8 a month to 1, despite the lack of human resources. All that it took was making patient safety their business and predicting who may deteriorate before the deterioration started.

Concluding remarks

Patient safety is a challenge for all. My journey from the first case I experienced as a young doctor has had many paths and experiences to allow me to define what it takes to be safe. I will end with another patient story. When I was a medical director in the obstetrics unit at a leading London hospital, a series of maternal deaths occurred. The obstetrics trainees had raised concerns about their learning and supervision in the months prior the first death. They did not use the words “we feel unsafe” and they did not have the psychological safety to do so. This was just before the emergence of patient safety as a science, and I now recognise that if we had patient safety knowledge then, it is possible that some of the women who died may have survived.

The lesson for me is that culture underlies patient safety, defines the way we work and can prevent harm. We all have a role to play and the eight actions can make a difference.